INTRODUCTION

As a chemistry professor at a liberal arts university, I find that between breadth of knowledge and depth of knowledge, breadth seems to have the advantage. CSU faculty are, after all, assigned to teach General Education courses which likely have little to do with any specialty we enjoyed when studying for our Ph.D.s. Moreover, my assignments at CSUDH have included stints in the Advising Center and the Offices of Cooperative Education and Telecommunications. My past sabbatical leaves also reflect this diversity. In 1978 I executed a project in computerized test development which evolved into a microcomputer version for which I wrote the software. The program, MICRO-SOCRATES, is still in use today. From 1980 to 1985 I mastered spoken French, finally in Paris at the Alliance Française, so as to be able to expand my circle of colleagues who were pursuing the application of computing to education in English- and French-speaking countries during my leave in 1985. In 1995 I executed a project in genetic engineering and microbiology at a national French laboratory, taking advantage of my fluency in French, my background in chemistry and biochemistry, three summers spent at UCSD working on the Human Genome Initiative and my knowledge of computational methods applied to scientific problems. My leave during the spring semester, 2005 took advantage of my active involvement since 1995 with the World Wide Web as an educational tool. Consistent with all of my Web offerings, it proposed to treat information as knowledge rather than as commodity. It took advantage of my background in science and my knowledge of the use of computers in education. Whereas my earlier leaves dealt with problems specific to computers and chemistry, cultural approaches to education and genetic engineering applied to various plant species, I was pleased, in the spring of 2005, to carry out a project which was, like each of my earlier sabbatical leave projects, something completely different.

Through my travels over the years I have captured thousands of photographs and slides of subjects useful for the courses I teach. Like so many professors, until I discovered the CSU IMAGE project I could envision all of the photos and slides I've captured initially to end up in boxes in the garage and soon thereafter to be transferred to a dumpster by my heirs. The IMAGE Project offers an avenue for such images to be shared with present and future colleagues. (1)

ON THE MATTER OF COPYRIGHT

Let us

begin with the following

three pairs of

images. Each pair is of the same subject, but in

each case the image on the left belongs to

someone and is intellectual property protected

by U.S. Copyright. (2) Each image on the right

was captured by me and has been offered to

CSU faculty, staff and students to be used for

non-profit educational purposes.

We are so inundated by images in the

modern world, both still and animated,

sight bites if you will, that their ubiquity at no charge deludes us into thinking that they are freely

available for our use. Nothing could be further from the truth. Claims of ownership and

copyright protection are more often than not made for these images. The matter of image

availability for non-profit educational use is not a trivial one. Although there

are tens of thousands

of images available on the Web and although they may be downloaded for informal personal use

and no one is the wiser, a public institution dare not offer these same images in an archive for

public use without risking unneeded and unwanted problems connected with the ownership of

intellectual property . It is not until an owner of an image states up front that it is being

contributed to an archive for unlimited non-profit educational purposes that the

institution shields itself from any threat of legal problems. The conduit leading from proprietary

interest to non-profit use has been opened by the CSU IMAGE Project so as to remove any doubt

about rights by faculty, staff and students to use these materials for their presentations and their

classes.

are tens of thousands

of images available on the Web and although they may be downloaded for informal personal use

and no one is the wiser, a public institution dare not offer these same images in an archive for

public use without risking unneeded and unwanted problems connected with the ownership of

intellectual property . It is not until an owner of an image states up front that it is being

contributed to an archive for unlimited non-profit educational purposes that the

institution shields itself from any threat of legal problems. The conduit leading from proprietary

interest to non-profit use has been opened by the CSU IMAGE Project so as to remove any doubt

about rights by faculty, staff and students to use these materials for their presentations and their

classes.

It is instructive to recall that an idea, along with ten other categories of human creativity (concepts, discoveries, methods, principles, procedures, processes, systems, theorems, work in which the copyright has expired, and work that the legal owner has placed in the public domain) may not be copyrighted. (3) The idea for each of these pictures, including the spot where the photographer stands to take it, cannot be copyrighted. Moreover, for the purpose of non-profit educational purposes, it doesn't matter if our contributed images are not award-winning photographs. All photographers want their works to be the very best, of course, but for the purpose of exemplifying classroom and laboratory topics, it is the topic which is of importance, not necessarily the quality of the image. The bottom line is that someone must capture an original image and to be willing to donate it to an existing public archive such as that of the IMAGE Project.

THE PRE-FUNDED PERIOD.

The project was divided between the pre-funded period, funded period and the post-funded period. Starting a year before the funded period, the spring semester of 2005, I became well acquainted with rules of cataloguing used by the CSU IMAGE Project and I reviewed IMAGE Project collections in the areas of science and technology, focusing on the categories of scientific instruments, astronomy, calendars, bridges and roads, chemistry, clocks and time, engineering and technology, light and heat, machines and automata, mathematics and measurement, product design, tools, transportation and architecture.

During this period, thanks to three private archives available to me (4), I catalogued and contributed selected images to the IMAGE project so as to become acquainted with the needs and transmission protocol required by the Project staff. I also traveled to Paris in June, 2004 so as to capture images of scientific instruments and technological innovations at the Musée des Arts et Métiers.

Space doesn't permit a narrative for more than a tiny fraction of the images which I have contributed to the collection, but to give the reader some idea of the wealth of image data which was available to me, I'll offer a few examples here.

This is the Pont des Arts in Paris (Oliver Seely, Jr.), dedicated in 1804 as the first iron

bridge built in that city. It leads from the Institut de France on the left bank to the Louvre on the

right.

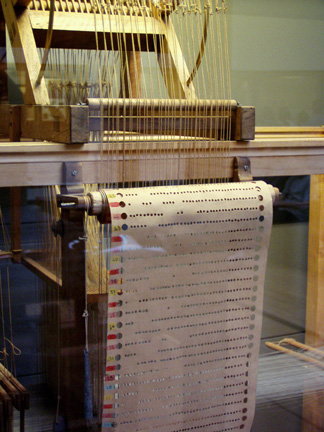

Basile Bouchon and Jean Philippe Falcon contributed to the development of the automatic horizontal loom which was finally perfected by two assistants to Joseph Marie Jacquard. The images on the left and right (Oliver Seely, Jr.) illustrate the technological development of the loom by Bouchon who used holes punched in paper on a long roll and Falcon who introduced cards using a similar coding procedure. Falcon's system was superior because torn cards could easily be replaced whereas Bouchon's system required whole rolls to be reproduced if one tear made a roll unusable.

These are "De

scheepsjongens van Bontekoe" (The Cabin Boys of

Bontekoe), the principal characters in the 1924 children's adventure

story by Johan Fabricius based on the journal of Captain Willem

Ysbrandsz Bontekoe about his voyage to Java in 1618. The original

chronicle gave a vivid account of the unparalleled adventure and

peril of transport and trade on the high seas in the 17th century.

Though the "Cabin Boys" became a best selling children's fictional

adventure when it was first published, the source material was

factual and exemplifies the position of world leadership in trade

enjoyed by the Dutch East India Company and the influence on that

trade of the sleepy (today) little port of Hoorn in Holland, little more

than a recreational marina smaller than either of the marinas in Long Beach, CA. The statues

which

stand on a quay at Hoorn gaze toward the North Sea allowing us to imagine their encounters with

strange

people and exotic lands in the South Pacific.

These are "De

scheepsjongens van Bontekoe" (The Cabin Boys of

Bontekoe), the principal characters in the 1924 children's adventure

story by Johan Fabricius based on the journal of Captain Willem

Ysbrandsz Bontekoe about his voyage to Java in 1618. The original

chronicle gave a vivid account of the unparalleled adventure and

peril of transport and trade on the high seas in the 17th century.

Though the "Cabin Boys" became a best selling children's fictional

adventure when it was first published, the source material was

factual and exemplifies the position of world leadership in trade

enjoyed by the Dutch East India Company and the influence on that

trade of the sleepy (today) little port of Hoorn in Holland, little more

than a recreational marina smaller than either of the marinas in Long Beach, CA. The statues

which

stand on a quay at Hoorn gaze toward the North Sea allowing us to imagine their encounters with

strange

people and exotic lands in the South Pacific.

Private archives more often than not yield photographs of events which are one-of-a-kind, either a look at a bygone era or an event so unusual that having it documented is important for the historical record. Here are some which fall into that category:

The Continental Baking Company in Long Beach, California was destroyed by the Long Beach Earthquake which is estimated to have measured 6.25 on the Richter Scale. (Oliver Seely)

In 1952, Mirror Lake in Yosemite National Park lived up to its name, as seen here at the right showing the symmetric reflection of Mt. Watkins. (Hubert A. McClain) Today, the spring snow melt still renews the lake fed by Tioga Creek, but the encroaching vegetation is said to be turning it into a meadow. (Oliver Seely, Jr.)

In October, 1966, the Pink Lady made her debut over a tunnel on Malibu Canyon Road and surprised and entertained northbound drivers. Highway officials were not amused; drivers were stopping along the road to gaze and there was the ever present danger of traffic accidents. Within 5 days the image was obliterated by 14 gallons of brown paint. By that time many enterprising photographers captured the essence offered by local artist Lynne Seemayer who felt that the Lady's spirit of abandon, frolicking naked on the beach with a bouquet of lilies, would offer a welcome respite to an otherwise mundane drive through Malibu Canyon. (Hubert A. McClain)

In 1972,

visitors to Stonehenge, the best

known of all megalithic sites, could still

walk and picnic between the prehistoric

monoliths. Soon thereafter, fearing that tourists and natives alike were loving the monument to

death, officials built paths encircling the site at a good distance so as to protect it from vandals,

graffiti artists and loving tourists. (Oliver Seely, Jr.)

In 1972,

visitors to Stonehenge, the best

known of all megalithic sites, could still

walk and picnic between the prehistoric

monoliths. Soon thereafter, fearing that tourists and natives alike were loving the monument to

death, officials built paths encircling the site at a good distance so as to protect it from vandals,

graffiti artists and loving tourists. (Oliver Seely, Jr.)

Over the years I have built Web pages for the classes I teach with exemplification where possible using still photos and videos. When the World Wide Web first rather exploded on the scene (didn't it, just?) around 1995 I saw the great potential for offering information to anyone with a connection to it, whether living in an industrialized or a third world country. My first offerings were tables taken from the Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, scanned, reformatted and converted to html format. My strategy was to pick a dozen or so tables of interest of a length not to exceed ten pages simply to learn the technique necessary to make this information available to Web users. I did it also to test the waters of the U.S. Copyright Law. A mentor of mine several years before had advised, "Ollie, you never make any progress unless you take a chance." I need not have worried, because the Feist Publications vs. Rural Telephone Services decision of 1991 reaffirmed, with Justice Sandra Day O'Connor writing for the majority, that facts simply cannot be copyrighted. (5) Since that time, when I can't find certain information on the Web, I search for it elsewhere and put it up with a link listed on my CSUDH Web page. All of my offerings can be found via links on that page. (6)

Of all the pages I have created, the Physical Properties of Woods and Composition and Properties of Alloys continue to generate a very large number of "hits" and more than a little amusement. Visitors to these pages erroneously believe that I am an expert on woods and alloys. I have had queries from motorcycle mechanics wanting to know details on aluminum alloys used in engine blocks to a cabinet maker in Puerto Rico who wanted me to advise him on a troubling rash caused by Teak dust.

My effort toward making information freely available on the Web continues to interest me. In 2002 I wrote a paper on the matter (7) - a contribution leading up to an on-line conference on Web-based video lecture demonstrations in chemistry - in which I observed

Although there has been a U.S. Copyright Register for 100 years, there is at this time no "public domain register."

Current law allows that a copyrighted work need not display a statement of copyright. Although based on sound logic (a work might be copied illegally having had its copyright statement removed), the law confuses the issue in the mind of the teacher interested only in educational use of information which appears in original works. One encounters a variety of material, including some in the public domain but not explicitly identified and some copyrighted but without a copyright statement attached. It is for this reason that all of my original Web offerings carry the statement (or an equivalent): "The text and photos on this page are in the public domain."

One day while looking for information on industrial pollution in the

San Gabriel River Channel, I

came across a link to the San Gabriel Mission and was struck by the absence of an image. Further

searching revealed that (at that time) there was no collection of

images of the California Missions on the Web. One of the three

archives available to me includes monochrome images dating back to

the 1950s of all 21

California Missions. I

scanned a few at low

resolution and created a

page. As luck would have

it, at that time for a limited

period, CSUDH was offered

Web monitoring software

and I found over the next

several months that the page

enjoyed a large number of

hits each day. A little

investigation yielded the

information that every 4th

grader in California studies the California Missions, so I

rescanned all of the images at high resolution and expanded my page. (8)

One day while looking for information on industrial pollution in the

San Gabriel River Channel, I

came across a link to the San Gabriel Mission and was struck by the absence of an image. Further

searching revealed that (at that time) there was no collection of

images of the California Missions on the Web. One of the three

archives available to me includes monochrome images dating back to

the 1950s of all 21

California Missions. I

scanned a few at low

resolution and created a

page. As luck would have

it, at that time for a limited

period, CSUDH was offered

Web monitoring software

and I found over the next

several months that the page

enjoyed a large number of

hits each day. A little

investigation yielded the

information that every 4th

grader in California studies the California Missions, so I

rescanned all of the images at high resolution and expanded my page. (8)

All of those images have now been contributed to the IMAGE Project. Here are two from that collection, at left is the Mission La Purisima Concepción at Lompoc and at the right the mission at Carmel. (Hubert A. McClain)

IMAGE CATALOGUING

An important part of the preparation for this sabbatical leave was the process of learning the method used to catalog images. The retrieval software at http://worldart.sjsu.edu works on a file created by Microsoft Excel. This file contains thirty-seven fields, not all of which need to be used for to catalog any particular image. (9) I added a thirty-eighth field, reference number, as a pointer back to the original raw image identifier. In preparation for the funded period a number of allowed identifying words needed to be added to field entries.

Several

fields led to ambiguities

which had to be worked out

during the course of the project.

"Creator" for example

sometimes referred to the

creator of the image rather than

the creator of the subject of the

image. The creator of

"Awaiting the End of

Prohibition" at the right would

be identified as the photographer (Hubert A. McClain), whereas the "Spruce Goose in Drydock"

at

the left would be identified as the builder (Howard Hughes).

The field "Art Form" might be identified as "photography" as in

the case of the image at the right, above, but as "sculpture" in the

case of "MU464" by Kengiro Azuma at the left.

Several

fields led to ambiguities

which had to be worked out

during the course of the project.

"Creator" for example

sometimes referred to the

creator of the image rather than

the creator of the subject of the

image. The creator of

"Awaiting the End of

Prohibition" at the right would

be identified as the photographer (Hubert A. McClain), whereas the "Spruce Goose in Drydock"

at

the left would be identified as the builder (Howard Hughes).

The field "Art Form" might be identified as "photography" as in

the case of the image at the right, above, but as "sculpture" in the

case of "MU464" by Kengiro Azuma at the left.

The fields "Subject, Object Type, Technique and Materials" usually referred to the subject of the image unless, as in the case of the image above right, the focus was on the creation of the image as an art form. Still, it was necessary in a number of instances to add appropriate entries where adequate identification of the field criterion demanded.

THE FUNDED PERIOD

The difference

between selecting images from existing collections for inclusion in the IMAGE Project

archive and of seeking to capture images having broad appeal needs

to be discussed briefly. Images in collections more often than not

are the result of the photographer having rejected a large number of

other images of the same subject before choosing to print the one

found in the final collection. The person who chooses such an image

to contribute is taking advantage of possibly many hours spent

toward achieving the final valued image. For example, the Grand

Teton at the left was the result of a five-day wait for the weather to

be just right to capture this remarkable image. (Hubert A. McClain).

The difference

between selecting images from existing collections for inclusion in the IMAGE Project

archive and of seeking to capture images having broad appeal needs

to be discussed briefly. Images in collections more often than not

are the result of the photographer having rejected a large number of

other images of the same subject before choosing to print the one

found in the final collection. The person who chooses such an image

to contribute is taking advantage of possibly many hours spent

toward achieving the final valued image. For example, the Grand

Teton at the left was the result of a five-day wait for the weather to

be just right to capture this remarkable image. (Hubert A. McClain).

It must be

accepted that some sacrifices will have to be made when

seeking original digital images for

the IMAGE Project archive. An

image may have to be captured

when conditions are not perfect,

with an understanding that it is

the subject matter which is of primary importance, not necessarily

the artistic excellence of the image itself. Consider, for example,

one of the sculptures which resulted from the International

Sculpture Symposium at CSU Long Beach in 1965, "Duet

(Homage to David Smith)" by Robert Murray. The image could

be legitimately criticized for the shadows which detract from the

geometry of the sculpture as well as the deterioration of the

surface. Still, the form and substance of the piece remains clearly visible. A contributor to the

IMAGE archive might argue that in the interest of seeing that images of these sculptures find their

way to the archive, some sacrifices have to be made and that we leave to future students, staff and

faculty the task of capturing stunning renditions for future generations.

It must be

accepted that some sacrifices will have to be made when

seeking original digital images for

the IMAGE Project archive. An

image may have to be captured

when conditions are not perfect,

with an understanding that it is

the subject matter which is of primary importance, not necessarily

the artistic excellence of the image itself. Consider, for example,

one of the sculptures which resulted from the International

Sculpture Symposium at CSU Long Beach in 1965, "Duet

(Homage to David Smith)" by Robert Murray. The image could

be legitimately criticized for the shadows which detract from the

geometry of the sculpture as well as the deterioration of the

surface. Still, the form and substance of the piece remains clearly visible. A contributor to the

IMAGE archive might argue that in the interest of seeing that images of these sculptures find their

way to the archive, some sacrifices have to be made and that we leave to future students, staff and

faculty the task of capturing stunning renditions for future generations.

Searching for

images suitable to be contributed to the IMAGE archive can lead down more than a

few blind alleys. I'm always on the lookout, particularly during the funded portion of this

sabbatical

leave, for useful images in the subject areas of science and technology, but it is not unusual to find

what appears to be a promising circumstance such as a museum

of oil well equipment in Taft, California only to have it turn out

to be little more than a theme park. I found no "photo

opportunity" there which could come close to the excitement

pictured by the gushing oil well during the oil boom of the

1920s on Signal Hill. (Thanks to Martha Ebersole Eads for this

dramatic photograph contributed to the IMAGE archive from

the collection owned by her grandfather, Dave Ebersole.)

Searching for

images suitable to be contributed to the IMAGE archive can lead down more than a

few blind alleys. I'm always on the lookout, particularly during the funded portion of this

sabbatical

leave, for useful images in the subject areas of science and technology, but it is not unusual to find

what appears to be a promising circumstance such as a museum

of oil well equipment in Taft, California only to have it turn out

to be little more than a theme park. I found no "photo

opportunity" there which could come close to the excitement

pictured by the gushing oil well during the oil boom of the

1920s on Signal Hill. (Thanks to Martha Ebersole Eads for this

dramatic photograph contributed to the IMAGE archive from

the collection owned by her grandfather, Dave Ebersole.)

It doesn't make sense on the one hand, in a project such as this

one, to travel a long distance with the intention of capturing a

single image only to find out that it is clearly less than one

expected. On the other hand, purposeful travel for capturing

images as they reveal themselves, though certainly more productive, is fraught with the possibility

of

unavailability. One productive way of going about the task is to peruse large numbers of travel

guides, tourist magazines, news reports and other pictorial material to find copyrighted images,

categorize them according to geographical area and to begin one's journey so as to be able to

capture

the very same images for contribution to an archive in the public domain. Even this strategy has

its

shortcomings. The collage below represents the best of three takes on successive days and in my

opinion is unsuitable for inclusion in the archive.

Notwithstanding the need to adjust the

brightness

and contrast of each segment so as to offer invisible transition from one to the next, it has

problems

of the ubiquitous smog of southern California, and on these particular days there was not a

crispness

to the image which one recalls having seen on earlier

occasions.

Notwithstanding the need to adjust the

brightness

and contrast of each segment so as to offer invisible transition from one to the next, it has

problems

of the ubiquitous smog of southern California, and on these particular days there was not a

crispness

to the image which one recalls having seen on earlier

occasions.

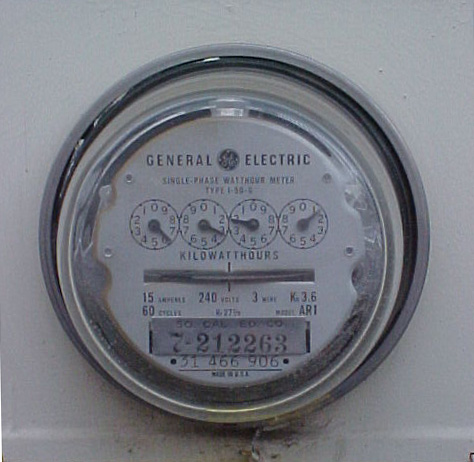

Moreover, pictorial guides are not going to give one ideas about important images to be captured in many areas of science and technology. Such guides simply won't contain for example the face of a kilowatt-hour meter which may be useful in any number of courses which cover subjects in science and technology.

One asks constantly if an image will be a valuable contribution or simply filler. At this early stage

in the life of the IMAGE archive I think one is safe to adopt the opinion that one person's junk is

another's treasure and to take the time necessary to capture for the archive such rather mundane

and "touristy" offerings such as the birthplace of President Richard M. Nixon, shown

here.

One asks constantly if an image will be a valuable contribution or simply filler. At this early stage

in the life of the IMAGE archive I think one is safe to adopt the opinion that one person's junk is

another's treasure and to take the time necessary to capture for the archive such rather mundane

and "touristy" offerings such as the birthplace of President Richard M. Nixon, shown

here.

Whereas the early stages of archive construction offer great

freedom to the contributor of photos, a developed archive

demands that the contributor avoid covering old ground.

One would anticipate that over the years of archive

development, the obvious

choices for contributed

images will be tapped first.

The sculpture "End of the Trail," in Visalia, the Picayune one room

schoolhouse in Coarsegold and the Wassama Roundhouse in

Ahwahnee are good

examples.

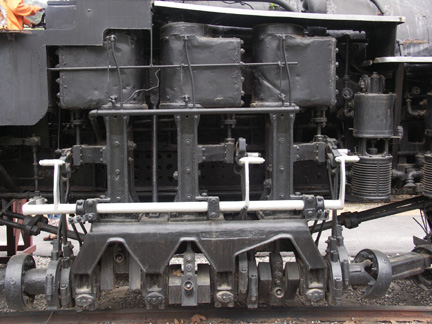

On the

other hand, even well

developed categories in

science and technology are likely to have many specific

topics not well represented. A good example would be

that of the Shay locomotive, designed and built by a

logger, Ephraim Shay, because the existing locomotives

had neither the

mechanical advantage nor the traction necessary to carry great

volumes of timber up

grades as steep as 6%.

The double acting pistons

transmitted force through

the piston shafts to cranks

spaced 120 degrees apart

to offer continual

pressure whatever the

position of the crank

shaft.

On the

other hand, even well

developed categories in

science and technology are likely to have many specific

topics not well represented. A good example would be

that of the Shay locomotive, designed and built by a

logger, Ephraim Shay, because the existing locomotives

had neither the

mechanical advantage nor the traction necessary to carry great

volumes of timber up

grades as steep as 6%.

The double acting pistons

transmitted force through

the piston shafts to cranks

spaced 120 degrees apart

to offer continual

pressure whatever the

position of the crank

shaft.

The piston shaft (1)

pushed the connecting

rod (2) along a slide to

operate the crank below.

The crank shaft turned

the wheels by means of

beveled gears acting on

the wheels at, in this case,

a step-down gear ratio of

2.25. The tender was

also included as a driving

vehicle by universal joints

between the two vehicles.

The

industrial revolution must have been a heady time for people

whose skills would have been wasted both before and after the

surge in industrial growth. Mathias W. Baldwin was one of those

whose skills and business acumen coincided with the needs of the

time. A jeweler and silversmith, Baldwin, George Vail

(ironworker, machinest and later a member of the U.S. House of Representatives) and George W.

Hufty, a machinist, went into a partnership in 1839 to form Baldwin, Vail and Hufty. Baldwin

had

been earlier engaged in the manufacture of bookbinders' tools and cylinders for calico printing. A

stationary steam engine was built on-site to power the factory tools. It performed so well that

Baldwin began to receive orders for ones just like it. In 1831 Baldwin was commissioned to build

a miniature steam locomotive for the Philadelphia Museum; its

great success with museum visitors led to an order for a real one

to run on a short line to the suburbs of Philadelphia. As luck

would have it, the Camden and Amboy Railroad Company

(C&A) had recently imported a locomotive (the John Bull) from

England but had not yet assembled it. Baldwin visited the

storage site and made notes of the dimensions of the parts.

This

simple exercise was the trigger event resulting in the partnership

which became the Baldwin Locomotive Works. The first

locomotive, the steam cylinders of which were bored by hand

using cutting tools embedded in wooden braces and worked by

employees who had to be taught the craft from ground up, was

mounted on a wooden chassis and drove wheels with wooden spokes and rims covered with a

cast

iron tire. It was put in use by the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad on

November

23, 1832 and operated successfully for around 20 years. At the right is locomotive #664 built by

Baldwin in 1899 and donated in 1953 by the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad to the

Travel

Town Museum in Griffith Park, Los Angeles.

The Copyright Problem Revisited

So as to remove all doubt about the hard

reality of the copyright and intellectual property conundrum

for educators, one weekend in April I traveled to Mt. Wilson to get some photos of the dome

housing

the 100-inch telescope. Like all journeys connected with this sabbatical leave, it was a thoroughly

enjoyable affair, though putting myself on the California freeways anymore than is absolutely

necessary carries with it an inherent insanity of our time. Every additional minute one spends

behind

the wheel increases the probability of an untimely demise. Still, it offered me an enjoyable

afternoon.

It turns out that the dome isn't visible in its entirety

from ground level. There are just too  many trees.

The

best place to be is at the top of the 150-foot solar

observatory. From that vantage point one can clearly

see the surrounding area. I did capture the image at the

left but then I wrote to two people, one a curator of

photo archives at the Huntington Library and the other

an astronomer with a key to the solar observatory. The

curator pointed me to the web site www.trove.net

which in no uncertain terms set the conditions for

downloading its images:

many trees.

The

best place to be is at the top of the 150-foot solar

observatory. From that vantage point one can clearly

see the surrounding area. I did capture the image at the

left but then I wrote to two people, one a curator of

photo archives at the Huntington Library and the other

an astronomer with a key to the solar observatory. The

curator pointed me to the web site www.trove.net

which in no uncertain terms set the conditions for

downloading its images:

"All rights, including copyright, in digital representations found on this site are held by RLG or its contributors. You may not copy, download, publish, display, crop, remove watermarks from, or otherwise alter or use any image on this site without RLG's express permission, with the exception of personal use (i.e., "fair use") to the extent it is permitted under U.S. copyright law. Once you have linked to any of the services provided for research or licensing, any use of an image is governed by the terms and conditions of that service."

This statement is approximately normal as regards the protection of intellectual property, but for my taste as an educator, it is far too restrictive. My approach, as you know by now, is to state up front "All of the images on this page are in the public domain. Copying is encouraged!"

The astronomer wrote back that there is a web cam at the top of the solar observatory which refreshes its image every few minutes and if any of those images would work for us we are free to use them. Most unfortunately, they are all low resolution images, and I told him I needed file sizes about ten times larger, but that if at any time in the near future he planned to host a group to ride to the top of the solar observatory, please to include me if at all possible. Meanwhile, what you see (above left) is what you get. The bottom line is to get one's own images when you find them if you do not want to be restricted in any way.

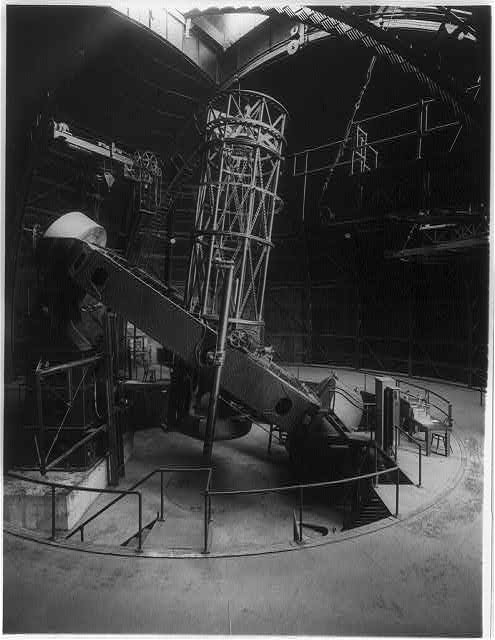

Still, not to

be dissuaded, I

visited the U.S. Library of

Congress page, www.loc.gov ,

and wrote a message to a

reference librarian asking if the

Library has a public domain

image of the domes and the

mechanism of the 100-inch

telescope. I was sent two low

resolution images, left and

right, and information on how

to obtain high resolution renditions, but the librarian added:

Still, not to

be dissuaded, I

visited the U.S. Library of

Congress page, www.loc.gov ,

and wrote a message to a

reference librarian asking if the

Library has a public domain

image of the domes and the

mechanism of the 100-inch

telescope. I was sent two low

resolution images, left and

right, and information on how

to obtain high resolution renditions, but the librarian added:

"Sometimes, after locating images, we are able to determine from the date or source that it is in the public domain; in other cases, we do not have sufficient information to tell, in which case it is up to you to assess the risks of using the image. In the case of the attached photos, we do not have any information as to who the photographers were or the sources of the photos."

So here is the

100-inch telescope, in use since 1917, and the Library of Congress does not have an

image clearly stated to be in the public domain of the mechanism or

of the dome which houses it. As

the statement above says, the

Library of Congress doesn't own

the images in their collection; the

images fall into several categories

of copyright protection.

There

are a number for which there are

no restrictions but most fall into

one or another restrictive

category. Here are a couple, left

and right from the Orville and

Wilbur Wright Collection. The image at the left is "Orville Wright at

the Pinnacles," and that on the right (with chemical stains) is

"Building at Kitty Hawk, September 26, 1902." The first is said to

have "No known restrictions," and the second "Rights status not

evaluated." In addition, the Wright collection includes categories of Airplanes, Family, Pets and

Dogs. As I wrote earlier, at this time (as in the case of the choices by the Library of Congress)

anything goes as regards submitting photos to an image archive (if you are Orville or Wilbur

Wright).

There

are a number for which there are

no restrictions but most fall into

one or another restrictive

category. Here are a couple, left

and right from the Orville and

Wilbur Wright Collection. The image at the left is "Orville Wright at

the Pinnacles," and that on the right (with chemical stains) is

"Building at Kitty Hawk, September 26, 1902." The first is said to

have "No known restrictions," and the second "Rights status not

evaluated." In addition, the Wright collection includes categories of Airplanes, Family, Pets and

Dogs. As I wrote earlier, at this time (as in the case of the choices by the Library of Congress)

anything goes as regards submitting photos to an image archive (if you are Orville or Wilbur

Wright).

More seriously, the Library of Congress has a mission to offer images which serve as "keys to a more complete understanding of the people, events, and achievements that have shaped the history and culture of the United States. . ." That is, the LOC decides what images constitute subjects consistent with that mission and potential donors need to understand the subtlety of accepting collections of images belonging to the estate of giants in the history of the United States even though such images coming from you or me might have little interest. That an image might be in the public domain is of lesser importance than the historical stature of the owner of the image's collection. Whereas a teacher asks "may I use this without restrictions," the LOC asks if the image is connected with an event which shaped our history and culture. To that extent, the copyright status of the collections of the LOC are of much lesser importance, except that they be stated when offering them to the public. Having access to a public image archive the entries of which lie unequivocally in the public domain is probably an idea whose time has come, though it will likely be slow to develop because of the lack of incentive (no profit motive) to create such an archive. Meanwhile, nothing is stopping amateurs from seizing the opportunity to assemble independent archives. Where photographs are free from recognizable human subjects so as not to complicate releasing them on the web without concerns about privacy, the possibilities are limitless and we need to get going.

Here are just a few of my contributions to finish out the funded period.

The soaproot plant which can grow to a height of 3 feet was used for glue, food, medicine, soap and fish poison by the California Mono Indians. The fibers which surround the root were useful in assembling a "soaproot brush" for cleaning granite mortars used for grinding acorns.

This four-lane bridge connects the west end of Terminal

Island to San Pedro, California. Named for the State

Assemblyman who served the San Pedro district, Vincent

Thomas served 19 consecutive terms for a total of 38

years. Crossing the Palos Verdes earthquake fault in

Long Beach Harbor, the bridge received a seismic retrofit

in 1998. As large as it appears to be, its span of 1,500

feet is only a little more than a third the length of the

Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. It is so obscured

by container cargo cranes and cruise vessels that some

scouting is necessary in order to find a decent viewing angle, such as the one above.

This four-lane bridge connects the west end of Terminal

Island to San Pedro, California. Named for the State

Assemblyman who served the San Pedro district, Vincent

Thomas served 19 consecutive terms for a total of 38

years. Crossing the Palos Verdes earthquake fault in

Long Beach Harbor, the bridge received a seismic retrofit

in 1998. As large as it appears to be, its span of 1,500

feet is only a little more than a third the length of the

Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. It is so obscured

by container cargo cranes and cruise vessels that some

scouting is necessary in order to find a decent viewing angle, such as the one above.

The historic project culminating in the successful completion of the Queen Mary ocean liner was interrupted by the Great Depression. The ship first set sail in 1936 and carried a maximum of 1,957 passengers and 1,174 officers and crew. After completing 1,001 crossings of the Atlantic Ocean it was retired from regular passenger service. Its last great cruise commenced on October 31, 1967 and ended in Long Beach, California on December 9, 1967 where it has served ever since as a museum and conference center.

The Société des Gens de Lettres offered

Auguste Rodin a commission for a

monument to Balzac in 1891. For seven years he prepared by reading

Balzac's works and biographies, attempting to understand the psyche of the

literary genius. After having carried out 50 studies, Rodin exhibited a model

in 1898, to scathing criticism and controversy. Not only was it lacking the

academic sculptural style of the time which demanded a finished surface, but

it ignored the expectation that Balzac's already great reputation be magnified

further by a noble visage. It is felt that the deep-set eyes convey the spirit of

Balzac's genius. This is cast no. 9/12 of 1967 which is displayed in the

sculpture garden of the Los Angeles County Museum of Modern Art.

The Société des Gens de Lettres offered

Auguste Rodin a commission for a

monument to Balzac in 1891. For seven years he prepared by reading

Balzac's works and biographies, attempting to understand the psyche of the

literary genius. After having carried out 50 studies, Rodin exhibited a model

in 1898, to scathing criticism and controversy. Not only was it lacking the

academic sculptural style of the time which demanded a finished surface, but

it ignored the expectation that Balzac's already great reputation be magnified

further by a noble visage. It is felt that the deep-set eyes convey the spirit of

Balzac's genius. This is cast no. 9/12 of 1967 which is displayed in the

sculpture garden of the Los Angeles County Museum of Modern Art.

The sculptor Jonathan Borofsky tells us he felt that Venice, California was an appropriate place "to put an image that deals with the duality within all of us. It's a male and a female mixed together--the male clown and the female ballerina, and the duality of performance: the street performer and the ballerina, the traditional, classical performer. A mixing of opposites [in a] splashy, showy kind of way." The Ballerina Clown is displayed at the corner of Main and Rose in Venice.

The pressure of corporate America is reflected in this

work showing a business man with his head buried in

the Citicorp Building in Los Angeles. It is said that

employees often touch this piece for good luck as they

pass by. It was sculpted by Terry Allen. Phillip Levine,

the poet, wrote,"They said to get ahead I had to lose my

head. They said be concrete & I became concrete.

They said go, my son, multiply, divide, conquer. I did

my best."

The pressure of corporate America is reflected in this

work showing a business man with his head buried in

the Citicorp Building in Los Angeles. It is said that

employees often touch this piece for good luck as they

pass by. It was sculpted by Terry Allen. Phillip Levine,

the poet, wrote,"They said to get ahead I had to lose my

head. They said be concrete & I became concrete.

They said go, my son, multiply, divide, conquer. I did

my best."

THE POST-FUNDED PERIOD

The Post-Funded Period will begin at the conclusion of the spring semester, 2005 and will continue into the foreseeable future as long as the IMAGE Project survives and continues to be maintained. My contributions during this period will commence in Paris during the month of June where in particular I will finish capturing images on the third floor of the Musée des Arts et Métiers which I failed to complete in June, 2004. July will be spent in Hampshire and Yorkshire, England capturing images of country homes and castles in the area. On return in the fall, I plan to submit every new image which has broad appeal for education to the IMAGE Project. My contributions during this immediate period and beyond will be on display at

and will be found by using the keywords osus (Oliver Seely, United States), osuk (Oliver Seely, United Kingdom) and osfr (Oliver Seely, France).

CONCLUSION AND OUTCOMES ASSESSMENT

The sabbatical leave project described above was thought-provoking, challenging and a celebration of generalism. It offered me an opportunity to honor the memory of three talented photographers in my family and to make sure that their best photographs would not be lost to future generations. It offered me an opportunity to visit many places which have close connections to the courses I teach, both in Chemistry and General Education and to capture images to be contributed to students and colleagues, both present and future, everywhere in the world where there is a connection to the Internet. It was an important exercise in educational outreach in the Age of Information. During the Pre-funded and Funded Periods, five hundred fifty original photographs, scanned emulsion negatives, prints and original digital images, were contributed to the IMAGE Project to be used by faculty, staff and students for non-profit education in the California State University.

*****

All of the examples of images printed in

this report are at low resolution with their reproduction having

been done either on a color laser printer or an ink jet printer. All images shown in this report,

except

those said to be copyrighted by others, or for which the copyright status is unknown, were

contributed

to the IMAGE archive at high resolution in JPEG format, starting at around 300 Kbytes at the

beginning

of the pre-funded period and rising to 3 Mbytes at the end of the funded period.

2. Fodor's Exploring Paris. Fodor's Travel Publications, Inc. New

York. 1993.

3. http://www.csudh.edu/oliver/subapp/

pubdom.htm

4. Hubert A. McClain, my wife's father, was a press photographer

for the Long Beach Press-Telegram and

later for the Times-Mirror Company. He was also a photographic hobbyist who specialized in

biological

and naturalist photography. A large number of his negatives and slides landed in our garage

following

his death in 1994. Oliver Seely was an industrial photographer, first for Bethlehem Steel and later

Todd

Shipyards on Terminal Island. His negatives of the 1933 Long Beach Earthquake came into our

possession following his death in 1991. Dorothy V. Seely taught her husband Oliver the art of

photography, having learned it from her father while an adolescent living in Santiago, Chile. She

worked

as the school photographer at several junior high schools in the Long Beach Unified School

District

during WWII when men who had earlier offered this service had been called to duty overseas.

For a time

Oliver and Dorothy owned Seely Photo on Anaheim Street in Long Beach. Oliver Seely, Jr. is in

his 38th

year as Professor of Chemistry at California State University Dominguez Hills. His collection of

photographs and slides used in his classess throughout his career make up the third archive of

photos,

selected items of which were contributed to the IMAGE project during the pre-funded period.

5. http://www.csudh.edu/oliver/sabapp/feist

.htm

6. http://www.csudh.edu/oliver/oliver.htm

7. http://www.csudh.edu/oliver/paper2.htm

8.

http://www.csudh.edu/oliver/galeries/missions/missions.htm

A. Accession Number

B. Historical Era

C. Nationality/Culture

D. Style/Period/Group/Movement

E. Creator Modifier

F. Creator Display Name

G. Creator Sort Name

H. Creator Role

I. Multiple Creators

J. Multiple Creators/Corporate

K. Art Form

L. Series Title

M. Title

N. Display Title

O. Subject

P. Object Type

Q. Notes

R. Technique

S. Materials

T. Measurements

U. Creation Date

V. Century

W. City/Site

X. Neighborhood

Y. Province/State/Area

Z. Country/Region

AA. Original Location

AB. Repository/Current Site

AC. Copyright Holder

AD. License.

AE. Web Access?

AF. Image Source Type

AG. Image Source Owner

AH. Image Source Date

AI. Cataloguer

AJ. Reference

AK. Institution & Date

AL. Reference Number