Teaching Secondary Reading

A Resource for Improving Academic Literacy with Adolescents ©2015

Schema Theory

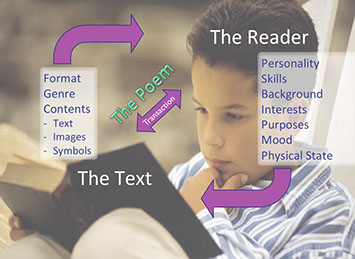

According to Transactional theory (Rosenblatt, 1978), the act of reading involves a transaction between the reader and the text. Each transaction is a unique experience in which meaning is constructed as the reader and text continually act and are acted upon by each other. The background, experience, knowledge, and interests of the reader are akin to the reader's schema. A schema has been defined as "a hypothetical mental structure for representing generic concepts stored in memory (Stein & Trabasso, 1982). More recently, more dynamic models of a schema-type process have been proposed (Gavelek & Raphael, 1996) that highlight the social construction of meaning.

According to Transactional theory (Rosenblatt, 1978), the act of reading involves a transaction between the reader and the text. Each transaction is a unique experience in which meaning is constructed as the reader and text continually act and are acted upon by each other. The background, experience, knowledge, and interests of the reader are akin to the reader's schema. A schema has been defined as "a hypothetical mental structure for representing generic concepts stored in memory (Stein & Trabasso, 1982). More recently, more dynamic models of a schema-type process have been proposed (Gavelek & Raphael, 1996) that highlight the social construction of meaning.

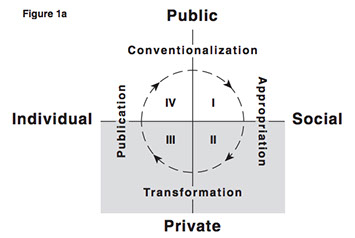

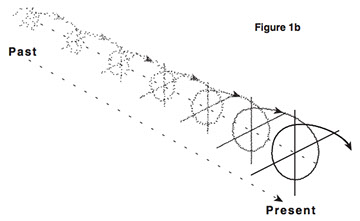

These newer models attempt to account for the many influences on the reader and her context, which thus impact meaning-making. For example, the figures below (Gavelek & Raphael, 1996, p. 186) illustrate the Vygotsky Space theorized by Rom Harré (1984), and highlight five features of this perspective: "1) it represents the relationship between discourse among students and between teacher and students; 2) it speaks to the idea that many voices contribute to an individual's learning; 3) it delineates how conventional knowledge supports invention; 4) it suggests reasons why creating an environment that fosters risk taking is critical to the development of higher psychological processes; and 5) it helps to explain that learning is not linear, nor does it develop in the space of a single event" (p. 185).

Figure 1a shows two dimensions, Public-Private and Individual-Social combining to define 4 quadrants (I-IV), which can define learners' cognitive functioning. Figure 1b is meant to demonstrate that learners move through these quadrants recursively, revisiting old learning and incorporating new. As Gavalek and Raphael (1996) describe it, this model helps us to "conceptualize the relationship between the discourse that students are guided to participate in through social venues and the text-related thinking that they independently demonstrate over time.... [W]e can see that language doesn't simply reflect thought; language makes possible what individuals think" (p. 188). Our classroom discussions are the way that knowledge is built.

In other words, in order to have high-quality learning, we must provide students with high-quality readings, and high-quality conversations about those readings. We must be accomplished readers and writers ourselves so that we can apprentice our young learners to higher order thinking.

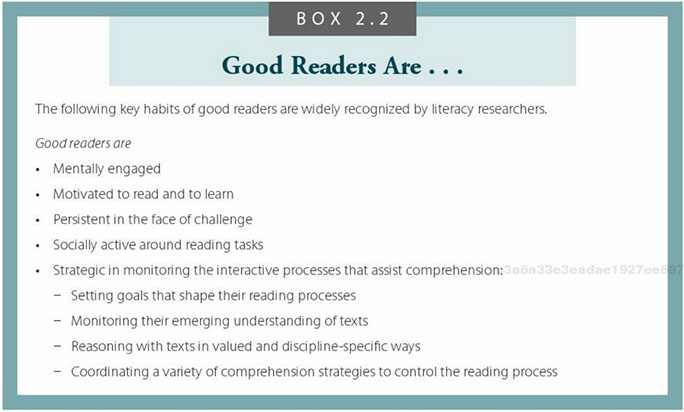

One approach to doing that is called Reading Apprenticeship (Schoenbach, Greenleaf & Cziko, 2012). In their framework Schoenbach et al. make some important assertions about reading. They note that "students often confuse reading with saying the words on a page. Reading is actually a complex problem-solving process that readers can learn" (p. 18). They note that good readers need much more than simply background and experience related to the reading topic. They also need social support for learning in order to become good readers. Their definition of "good readers" is below (p. 21).

The Reading Apprenticeship Framework formally acknowledges the multidimensionality of learners, and holds the classroom community accountable for not just improving student knowledge and skills, but for showing students how to "develop the learner dispositions to engage and persevere as independent readers, writers, and thinkers." The development of confident and competent learners is a social accomplishment, achieved when teacher and students are aligned in their learning goals and classroom culture.

WestEd publishes Reading for Understanding, which includes these downloadable resources.

The views and opinions expressed on unofficial pages of California State University, Dominguez Hills faculty, staff or students are strictly those of the page authors.

The content of these pages has not been reviewed or approved by California State University, Dominguez Hills.